Highbridge Music Ltd.

Highbridge Music Ltd.

Studio 6, 18 Kensington Court Place, London W8 5BJ, UK

Email: howard@howardblake.com

*AUTOBIOGRAPHY op.428 (December 2017)

TITLE: 'WALKING IN THE AIR CAN BE DANGEROUS'

Published by: Highbridge Music LtdNote on Lyrics: Copyright Howard Blake - bound version available by order

Contents

- Howard Blake born Enfield, London (1938)

- Cuffley and the Blitz (1941)

- Move to Brighton (1944)

- Choirboy (1945)

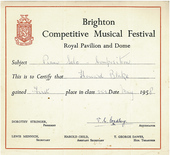

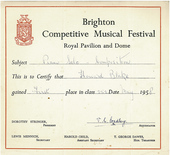

- Preston School of Music and my first music certificate (1946)

- MARCH IN D (1949)

- Solo soprano in Gilbert and Sullivan's 'Ruddigore' - as ROSE MAYBUD (1950)

- Solo soprano in Edward German's 'Merrie England' - as BESSIE THROCKMORTON (1951)

- Solo soprano in G&S's HMS Pinafore as JOSEPHINE THE CAPTAIN'S DAUGHTER (1952)

- Solo contralto in G&S's 'Yeomen of the Guard' - as DAME CARRUTHERS (1953)

- 'IT WAS A LOVER AND HIS LASS' (1954)

- PIANO FANTASY (1955)

- PARTY PIECES, PIANO TRIO NO.1, BURLESCA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO (1956)

- EARTH AND AIR AND RAIN, FAREWELL MY NANCY (1957)

- VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF BARTOK, JAMES JOYCE SONGS,TWILIGHT WALK,AUBADE (1958)

- PRELUDE, SARABANDE AND GIGUE (1959)

- REMEMBRANCE MARCH, BLUE SEA AND EVENING SKY (1960)

- FOUR MINIATURES, SYMPHONIC EXTRACT (1961)

- 'A FEW DAYS' - 16mm. film with script, music and direction by Howard Blake. (1962)

- PRELUDE IN B MINOR (1963)

- PIANO TRIO NUMBER 2, LATIN MOON (1964)

- 'HAMMOND IN PERCUSSION' EMI album, 'THE SHARK' (1965)

- Recording with 'THE SCAFFOLD' and PAUL McCARTNEY (1966)

- THEME MUSIC, PETER COLLINSON,'RED, WHITE AND ZERO' (1967)

- THE LOST CONTINENT, A TWISTED NERVE (1968)

- SOME WILL SOME WON'T, AN ELEPHANT CALLED SLOWLY (1969)

- film: 'ALL THE WAY UP!' (Live bbc tv) 'MUSIC NOW' (1970)

- Move to the Sussex countryside (1971)

- tv: 'THE UP-AND-DOWN-MAN' (1972)

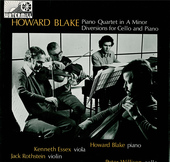

- THREE SUSSEX SONGS, DIVERSIONS FOR CELLO AND PIANO, THE ROTHSTEIN VIOLIN SONATA (1973)

- PIANO QUARTET, SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO ballet:REFLECTIONS (1974)

- THE SONG OF SAINT FRANCIS, STRING TRIO, THE STATION (1975)

- DANCES FOR TWO PIANOS, TOCCATA - A CELEBRATION OF THE ORCHESTRA (1976)

- films: 'THE DUELLISTS', 'STRONGER THAN THE SUN' (1977)

- baritone & harpsichord: 'TOCCATA OF GALUPPI'S', FLUTE CONCERTINO (1978)

- Ballet:THE ANNUNCIATION. choral: 'FROM THE CRADLE TO THE GRAVE' (1979)

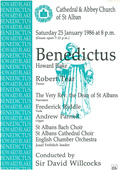

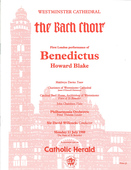

- 'BENEDICTUS' A DRAMATIC ORATORIO (World premiere,Worth Abbey) (1980)

- SINFONIETTA FOR 10 BRASS, ELEGY FOR SAXAPHONE QUARTET (1981)

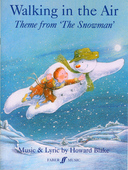

- THE SNOWMAN - a 26-minute animated film where the script is the music (1982)

- 'BENEDICTUS' IN AUSTRALIA. SNOWMAN CD ON CBS MASTERWORKS (1983)

- CLARINET CONCERTO, NURSERY RHYME OVERTURE, 'WRECK OF THE JULIE PLANTE' (1984)

- 'DIVERSIONS' FOR CELLO AND ORCHESTRA , 'FUSIONS' FOR BRASS (1985)

- 'GRANPA',Prix Jeunesse:'Honeybee and the Thistle' for Prince Andrew & Fergie (1986)

- Three Choirs Festival commission, 8-part FESTIVAL MASS a cappella. (1987)

- Overture: 'THE CONQUEST OF SPACE' - to launch the European Astra satellite (1988)

- Concert premiere: 'GRANPA' with The Philharmonia and London Voices (1989)

- CHRISTMAS LULLABY for 2 sopranos and ensemble. JUBILATE DEO for choir and organ (1990)

- PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA - HRH PRINCESS DIANA'S BIRTHDAY COMMISSION (1991)

- VIOLIN CONCERTO (1992)

- 'THE LAND OF COUNTERPANE' (1993)

- ALL GOD'S CREATURES, LA BELLE DAME SANS MERCI, LE GISANT (1994)

- 'CHARTER FOR PEACE', 50 years of The United Nations in the presence of The Queen (1995)

- EVA - A BALLET ABOUT WOMAN, film: 'MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM' (1996)

- THE BEAR - 'SOMEWHERE A STAR SHINES FOR EVERYONE' - CHARLOTTE CHURCH (1997)

- 'IF' - RUDYARD KIPLING'S POEM WITH MASS CHOIR,ORCHESTRA,BAND OF THE GHURKAS (1998)

- 'MY LIFE SO FAR' - (1999)

- 'JACK FROST AND THE ICE-PRINCESS', Snowman Stage Show triumphs with new Act 2 (2000)

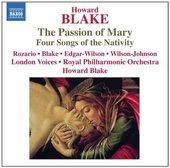

- STABAT MATER (later renamed 'The Passion of Mary') (2001)

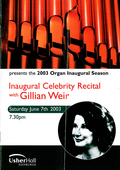

- 'THE RISE OF THE HOUSE OF USHER', a mighty organ piece for Dame Gillian Weir (2002)

- 75th birthday concert in the Wigmore Hall (2003)

- 'SONGS OF TRUTH AND GLORY' for Three Choirs Festival, 'Benedictus' in Stockholm (2004)

- HRH Sultan Idris of Selangor, Kuala Lumpur and SULTAN'S SONG (2005)

- oratorio 'THE PASSION OF MARY', soprano 'ODE TO SLEEP', piano 'HAIKU' (2006)

- MADELEINE MITCHELL (VIOLIN) AND HOWARD BLAKE (PIANO) RECORD AN ALBUM FOR NAXOS (2007)

- 'SPIELTRIEB' A STRING QUARTET IN FOUR MOVEMENTS (2008)

- 'SPEECH AFTER LONG SILENCE' (2009)

- 'DIVERSIONS' FOR CELLO AND PIANO (2010)

- 'SPEECH AFTER LONG SILENCE' (2011)

- 'JAMES JOYCE SONGS' - tenor Richard-Edgar Wilson (2012)

- 'ELEGIA STRAVAGANTE' (PIANO TRIO NO.3) (2013)

- THE LAND OF COUNTERPANE - an animated film (2014)

- 'PASSION OF MARY' IN SALISBURY CATHEDRAL (2015)

- WOMAN WITHOUT A NAME - a full evening ballet in two Rheinland opera houses (2016)

- 'SLEEPWALKING' WITH KATHERINE JENKINS (2017)

- COBLENZ FESTIVAL CELEBRATES HOWARD'S MUSIC (2018)

- WALKING IN THE AIR FOR SOLO VOICE AND A CAPPELLA CHORUS (2019)

- SOLILOQUY FOR SOLO CELLO (2020)

- SCHERZO IN JAZZ, THE RISE OF THE HOUSE OF USHER (2021)

- CONCERT WITH LANA TROTOVSEK (2022)

- Sinfonietta for brass, The Avengers, The Duellists, Chamber Music (2023)

- Index

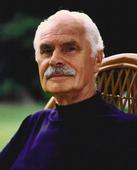

Howard Blake born Enfield, London (1938)

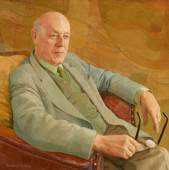

PREFACE: written in 1991 by musicologist, orchestrator, author and critic, Christopher Palmer OBE (1945 -1995), a great friend and insightful supporter to whose memory this autobiography is affectionately dedicated.

'Most composers, like other people, have to earn their own living once their training is completed and, from the 1920's on, many such professionally-trained composers welcomed the opportunity to write for radio, film, television and other media outlets. One of two things generally happened to these composers: either they gave up composing their 'own' music altogether, or - more often- the one career ran parallel to the other. What was almost unheard of was for a composer deliberately to abandon a flourishing career in media-music, in mid-course, in order to devote himself exclusively to his 'own' or 'real' music. Yet this is what Howard Blake did. What is even more unusual is that far from disowning his alter ego, the kind of musician he was and the kind of music he produced for the first ten years of his professional life, he found in them the mainspring of a remarkable personal renaissance. Much of the raw material of his most significant works -the Toccata for Orchestra and the Piano Concerto- derive from this source, but so refined, processed, enhanced, sublimated, as to be scarcely recognisable. The end product has a deceptive simplicity not unlike that of Mozart. I mention Mozart advisedly since the classical qualities implicit in scores like 'The Snowman' and the 'Diversions for Cello' are on full frontal display in the 'Piano Concerto' . There is a child-like exuberance and spirit of delight...but a shrewd supervisory intelligence plots every move...and never allows the plain, ordinary, even commonplace musical language it speaks ever to sound plain, ordinary or commonplace. Much of this is due to a strong feeling for line, and not just melody. Counterpoint is far more the essence of Blake's music than harmony. To cast a full-scale concert work in a simple diatonic style with no sense of deja vu is a considerable achievement.'

WALKING IN THE AIR CAN BE DANGEROUS

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY WRITTEN BY COMPOSER HOWARD BLAKE,OBE,FRAM.

My great-grandfather on my mother's side was Henry Andrews, born in 1832, who began life as a journalist but became a notable non-conformist preacher, pastor of the Quay Congregational Church in Woodbridge, Suffolk from 1870 to 1887. His wife Harriet Augusta (nee Thurston) was musical and played the organ. Their second daughter, born in 1866, the high-spirited Leisa Lovely, was my grandmother, and she inherited the musical gene, singing and playing violin and piano.

She married Leader, son of Funston Benson, the owner of a family firm purveying high-class leather goods at establishments around London. Leader ran one at 70 Upper Street,Islington, the large silver BENSON sign remaining until late in the twentieth century. He was a gentle soul who played the flute, a talent passed on to his son, my uncle Alec. Alec's two older sisters, Gladys and Dolly, played the piano a little, but real talent was inherited by my mother, their younger sister Grace, both as pianist and violinist. Unfortunately, where her mother abounded in self-confidence, Grace was timid and self-deprecating. In early 1914 at the age of 17 she was invited to join the prestigious Queen's Hall Orchestra as a violinist, but was too shy to accept. With the outbreak of war the boys whom she had grown up with were prime officer material and eager to join up. Many left for the trenches and some didn't return.

At fifty Leader died of a heart attack whilst cranking a car by the Hugh Middleton statue at Islington Green and my unpredictable and most inconsiderate grandmother sold the business, acquired a new husband and went to live in the South of France. Grace was left to fend for herself and the disintegration of her home was a loss and a shock. She would recall her early life in Islington with deep affection: the Agricultural Hall where she could hear lions roaring when the circus came; Collins Music Hall echoing with the sound of laughter and applause; The Biograph on the corner showing silent films with piano; walking in column to Union Chapel on Sundays, her father in a silk top hat, arm in arm with her mother, the four children marching behind, a maid and errand-boy bringing up the rear.

Her cousin Dora Rowse was a pianist and music teacher whose husband played the organ at the Alexandra Palace: another cousin, Mary Holder, was an actress in the Frank Benson Shakespeare Company in Stratford-on-Avon, once playing Celia to Tallulah Bankhead's Rosalind in 'As you like it'. She married Jack Bligh, an actor and film stunt-man and a great friend of Charlie Chaplin. She wrote novels and, when they moved to South Africa in the Thirties, founded a theatre company in Johannesburg and broadcast talks on radio. Her cousin Ivan Andrews in Muswell Hill gained a PhD at 22 and pioneered diesel technology. But he too had the musical gene, playing excellent Bach on the piano and visiting Bruges to play carillon in church steeples as a holiday pastime.

Grace got a civil service job in the Accountant General's office of the GPO where she was befriended by office superintendent Constance White and her sister Elsie, committed members of the Plymouth Brethren. She took lodgings near them in Ealing, went to meetings and became immersed in this very narrow religion. Constance and Elsie loved 'little Gracie' and they took her everywhere with them. The shock of her family's sudden disintegration and the behaviour of her mother no doubt assisted her descent into this change of belief pattern. She had lost her family but found another with the Brethren.

Plymouth Brethren hold the strictest of puritanical outlooks; one should only pursue that which is 'profitable in the sight of God'; one's 'yea' should be 'yea' and one's 'nay' should be 'nay'; 'to lie to anyone is to lie to God and He will punish you'. They don't believe in unprofitable pastimes like the cinema, or romantic novels, or the theatre, or dancing, or love songs or the playing of music - unless it is the simplest of hymns, sung purely to the glory of God, hymns sentimental and (to my mind) vulgar, such as those of Sankey. For my mother to have to play and sing this sort of material after an upbringing in classical music must have been hard, but she took it, and by the time she was introduced to a devout young Brethren preacher, she seemed to have lost any rational defence system that might have given her second thoughts.

Horace Claude Blake, my father, also worked in the Post Office and also attended the White sisters Brethren meetings, often preaching. He met Grace there and also had lodgings in Ealing, waiting at the underground station to travel in to work with her and one day proposing on the platform at Ealing Broadway. He explained that he had ceaselessly prayed for God to give him guidance and God had told him that he should marry her. My mother felt she had no choice. How could she go against God? I am inclined to think that she didn't love Horace, in fact maybe she didn't much like him either, and no doubt thought that her well-spoken family would probably not like him much either.

She was right and, once they'd married, her family started to drift away from her. I was never to meet Dora Rowse or her husband who played in the Alexandra Palace. I met her cousin, Dr.Ivan Andrews PhD., only by chance more than 50 years later, just before he died. His cousin Sybil, whom I'd never even heard of, approached me after the premiere of 'Benedictus' in St. Alban's Cathedral in 1998 and asked if I had a grandmother called Andrews. She was amazed to learn that I was a musician and composer 'despite my background'. My father had been regarded by much of Grace's family as 'beyond the pale' and Grace had to learn to manage without their support.

Horace had grown up in Broadstairs, his father devoting his life solely to God by being the leader of a sect of the Brethren, gaining a meagre living by acting as companion to an old Brethren member. Bible reading began at breakfast when after grace each family member must read a passage from the Bible, passed solemnly around. One also had to invent prayers, which I experienced once or twice and found unbearably embarrassing. His mother, my grandmother, had given him six children whilst also running their home as a boarding-house. A wealthy PB member seems to have provided funds to educate the oldest son, my uncle Harry, who was sent to Simon Langton's in Canterbury, deserted the brethren, studied medicine and became Doctor H.E.Blake MD, a succesful Harley Street surgeon, later marrying as his second wife - Lady Valerie French, grand-daughter of Field Marshall Sir John French, Baron Ypres.

But Horace as the second-eldest son received no assistance and had only seven years of school, from six to twelve. He made the most of it, at the end of his life being still able to quote the funeral oration from Julius Caesar, adept at multiplication and division and able to sight-sing or play hymn tunes using the tonic-solfa method. At twelve he started working as a telegraph boy earning one farthing per telegram delivered yet giving one-third of the proceeds to the family. Like all Brethren he was respectful and hard-working and with the help of evening classes took City and Guild exams and gained a position at the local telegraph office where he also learnt the Morse-Code.

On outbreak of the First World War he was conscripted by the army but refused to fight. Summonsed to appear in court he explained to the judge that whilst loyal to King and Country his religion forbade him to kill people under any pretext. The judge asked if he would be prepared to work as a non-combatant in the front line but forfeit the protection of carrying a gun. He agreed and was sent off to Ypres in Belgium as a private in the Sappers, detailed to lay cables at the front line. As shells and bullets whistled around him he continually prayed to God to protect him (which He obviously did!) since he emerged from the war without a scratch. However, the period in the front line had not lasted too long because, when it was discovered that he was a brilliant operator of the Morse-Code, he was moved to the interception of enemy messages and proved invaluable by intercepting them.

After the war he was taken on by the Central Telegraph Office in London. His spare time was taken up by preaching and Grace was the first woman to whom he proposed. They married in 1927 when they were both thirty, considered quite old to start a family, although it wasn't immediately clear that they wanted to. Horace was monumentally energetic in his work, his self-advancement and his evangelism. They moved to Enfield, where I believe my maternal grandmother helped them finance the building of a house at 223 Southbury Road. Horace commuted to Central London, worked a five and a half day week, took endless evening classes and, in whatever spare time there was, ran 'The Brigadier Hall' assisted by Grace - a Christian charity centre for poor London children. They taught them the Bible, fed them tea and buns, organised swimming galas and took them on holidays to Southend and Clacton in the summers.

Brethren thinking did not permit Grace to keep her job, once she had married and had children. She kept house for the family. There was an upright Godfrey piano used for nothing but Sankey-type hymns, and her violin which was locked away because she was forbidden to play it. Her brother and sisters did sometimes visit but on the whole her life revolved around the Brethren. She was gentle, quiet and very shy and had no idea how to stand up to her husband.

It is possible that I might never have been born at all if it had not been for the intervention of my rumbustious grandmother, then living in Nice. She suggested to a friend there, a Mademoiselle Peters, that she might like to visit England and stay with her daughter and son-in-law in Enfield in order that she might learn English. The two women got on famously and my mother followed her suggestion of seeking medical advice. Attention to her Fallopian tubes followed and resulted in the birth of my brother Philip one year later. She was thirty-eight years old.

My father was thrilled with his first-born and innumerable photos show joy in a face ever-previously solemn, while Philip smiles and laughs and chortles with glee, giving no clue to future worries.

Three years later I became the third male Scorpio in the house. Quite a few happy early photos exist of me, but the happiness on Philip's face has faded. He is a bystander. He had had three years of total individual adulation and attention, and suddenly it had changed. Where Philip took after his father, I took after my mother. The opposing natures of the parents were written large in their sons. Where Philip was clever, rational and serious, I was instinctive, irrational and cheerful. I was adored by my mother, Philip was adored by his father. But he was so much like his father that this caused tremendous tension, Horace seeing his own strengths and failures and, not wishing to be shown them, trying to correct them. On a visit to Palm Springs in 1994 I was introduced to a Mexican woman with psychic gifts, a companion of John Wayne's. She knew nothing about me at all but after a long time in silence said: 'Your whole life has been shadowed, affected and in some ways determined by sibling rivalry'. How could she possibly know that? It's true that I fought and rowed with Philip, but with my mother was never anything but happy and I have no memory of ever once falling out with her. She was so musical, so gentle, so humorous.

Cuffley and the Blitz (1941)

A LION CALLED WINSTON

The second world war broke out before my first birthday and it occurred to my father that living next to the armaments factory in Enfield might not be the safest place. He decided to move his young family a little out of London to Cuffley in Hertfordshire for the duration of the war, thinking it wouldn't attract Hitler's bombs. In fact it did attract a few since the Lufwaffe tended to drop leftovers once they had crossed London and wanted to get home fast. We lived at first in a bungalow off the village high street, where in the next door garden a man kept a lion called Winston! My father could not see that having two babies next to a full-grown lion was in any way dangerous. He was more disturbed when we woke up one morning to find that the fish-and-chip shop opposite had been hit by an incendiary bomb and burnt to the ground.

THE MINISTRY OF INFORMATION

Much to everybody's surprise, my father, who had once seemed somewhat unsupportive of War, King and Country, was suddenly and unexpectedly appointed as head of telephonic communications in the Ministry of Information, the hub of wartime espionage, roguery and trickery. He worked high secret at Senate House, commandeered from this London University building for the duration, where served a host of eminent men such as Sir Winston Churchill, Lord Duff Cooper, General Mark Clark and Baron Sir Leslie Hore-Belisha MP. An amusing highlight of Horace's career was his oft-related story of a summons to the office of General Mark Clark:

Clark: 'There's a war on Blake and all I've got is one goddam phone on my desk. What the hell's going on?'

Horace: 'The reason you only have one phone is precisely because there is a war going on!'

He was never one to argue with.

Another story was of the notorious lady's man, Lord Duff Cooper, graciously opening a door for a very pretty young girl typist, who ignored and swept past him without a word.

'Oh, oh, she cuts me!' he cried.

CUFFLEY, HERTS.

We moved to Cuffley, a village in Hertfordshire where my father rented a detached house at 82 Tolmers Road, whose owners had left the country for the duration of the war. It had a garden with a pond, a little apple orchard and a nice view across a cabbage field to a railway embankment. Leisa Lovely Cotching, my grandmother as she was now named, came to live with us, her second husband having died and curiously left her penniless. I wondered why? A multitude of expensive trunks and cases went up into the loft, their sides plastered with labels saying Hotel Splendide, Cunard Line, Biarritz and so on - which might have had something to do with it. My father was less than pleased to see her, but I adored her at first sight, with her absurdly youthful brown wig, her cheeks rendered glowing with cochineal, her foxhead-wrap that bit its tail with a silver clasp, and her innumerable stories.

'Why do you have a crooked nose Grandma?'

'I came out of the Negresco Hotel one morning, the door of the limousine was opened for me but the chauffeur closed it a little too rapidly and my nose was trapped in the door. I was on my way to a party given by the Admiral in his battleship harboured in Villefranche. We decided to play song-charades - acting out titles of well-known parlour songs for people to guess. I took three coconuts from the dining-room and laid them on the centre of the state-room carpet. Absolutely nobody could guess!'

'What was it, Grandma?'

'Where my caravan has rested!'

She would sit at the piano and play and sing:

'...but the clock (rapping on the piano lid) - stopped (rap)- never to go again when the old man died'

..and we would join in:

Fifty years and never stopping, tick-tock, tick-tock Fifty years and never stopping, tick-tock, tick, but the Clock (rap) - stopped (rap)- never to go again when the old man died.

I sat in front of the fire with her and cut out cartoons of Hitler from newspapers, pasting them into a scrap-book:

A parrot is sitting in its cage and a cat lying on the floor says:

'I don't mind you purring, but I don't like it when you stop.'

We would listen at night to the purring of buzz-bombs (V2 rockets) and think the same and one night the purring did stop. The almighty explosion blew out all our windows, cracked the ceilings and made a crater which looked 100-feet deep. In the morning we walked through the cabbage-field to see it and all the village were there. It had landed just beyond the embankment, which had saved us from the blast. My father had obviously been praying again.

I have another clear memory of my mother pushing me in a pram down the hill to the village and encountering the most glorious smell of bacon wafting across the countryside. We arrived at the grocer shop to find it burnt to a cinder by an incendiary bomb and all the food merrily cooking in the ashes. In the garden we would pick up silver paper streamers and flak from overhead gun battles. We slept under the stairs and presumed that having wars was the normal way that life was lived. Hitler was demonized and we thought he was the Devil. For a long while I believed germs and Germans were the same thing. I had a little flick-book of Hitler with a demon's tail standing on top of the world and as one flicked the world rolled over and crushed him.

A VISIT TO BEDNALL FARM, STAFFORDSHIRE.

My uncle Alec Benson played the flute and lived in a tiny village called Bednall near Cannock Chase in Staffordshire with his wife Cissy and his son, my cousin Peter. At the height of the blitz Philip and I were sent there to keep out of harm's way. From my point of view this was not entirely true. The first thing my brother did was push me into a field full of stallions, which frightened the life out of me, although fortunately they didn't attack. Next he locked me into a pigsty on the nearby James's farm, with sows four times my size. I was rescued in the nick of time by Doris James, the farmer's wife. Back in Cuffley he threw all my toys onto the fire, causing a chimney alarm and calling out the fire brigade. One day we all went for a picnic in Epping Forest where Philip left his favourite toy, a white terrier called Jock, sitting in a tree. In the middle of the night he began to scream and scream for it until at four o'clock in the morning my father had no option but to go back and retrieve it. Philip also started to suffer from nettle rash - so severe and persistent that sometimes he had to have a nurse. Invited across the road one day to play with some neighbour's children we sat on a big swing-chair by a pond. He gave it an almighty push and I fell in, running home dripping wet, contracting double pneumonia and gaining a propensity for chest problems which stayed with me for some years. It seemed he did not much like having a brother and was doing his best to say so.

A CHANGE OF RELIGION

Moving to a village affected my father in a most surprising way. He changed his religion. I suppose that for one thing the Plymouth Brethren could no longer get to him so easily. Petrol was heavily rationed and journeys were only supposed to be undertaken if vital to the war effort. When at the age of four I nearly died of bronchial pneumonia there was a great stir in the village when my uncle Harry drove up in a magnificent white Riley 12. Surely he shouldn't be driving? But Uncle Harry, my father's brother, was in fact a distinguished Harley Street doctor and one of the few people perfectly entitled to drive in war time. This fact might well have saved my life! He attended to me and I recovered.

In fact I think Horace was pleased to get away from the brethren. The acquisition of a wireless (which had been outlawed when he was with the Brethren) had affected him and he started to want to sing like the tenor Richard Tauber, or go to see a West End show, or do some amateur dramatics. There was a small, black tin church near us which was pretty 'low'. He enquired about beliefs and was presented with a copy of 'The 39 Articles of the Christian Faith' which he told us were 'sound' and on Sunday afternoon July 4th 1943 we were all obliged to get baptised into the Church of England one after the other. I remember feeling that I was too big for it. Getting baptised was for babies and this was embarrassing. Whether my mother had any say in the matter I don't know; after all she had given her whole way of life up to commit herself to the Brethren because Horace was a shining light in it and that's why she'd married him. He was moving the goalposts. Later this was to bother my brother a great deal, but for the moment it produced what I personally could only see as a tremendous improvement!

A wind-up HMV gramaphone appeared with 'You are my heart's delight' and 'This is my lovely day'. We could play 'The Teddy Bears Picnic', 'The March of the Tin Soldiers','The Rose of Tralee' and all sorts of nursery rhymes. My mother began to play Chopin and Beethoven after we'd gone to bed and then one day we went to the cinema in London to see the sumptuous story of composer Johann Strauss: 'The Great Waltz' starring Luise Rainer. If ever a film could persuade one that being a composer was glamourous it would have been 'The Great Waltz' and perhaps somewhere this thought entered into my head?

Sixty years later in London a tiny little lady dressed from head to foot in white was introduced to me by ballet-critic Nicholas Dromgoole. 'I am Luise Rainer and I have come to meet you dressed as 'The Snowman!' she said. She was still acting at the age of 95 having been the only actress in history to win the Oscar for Best Actress two years running. ('The Good Earth 1937 and 'The Great Waltz' 1938.)

Childrens' books with pretty covers appeared alongside the Bible and my mother joined a well-stocked lending library. Horace was trying to make up for a lost life, but despite outwardly accepting a more conventional faith he remained Plymouth Brethren at heart. He was opposed to financial gain, business, mixing with wordly people, success, fame, being clever, showing off, freemasons, astrology, spiritualism, magic, gambling, the stock market, sexual intercourse other than for procreation, intimacy, physical contact between members of the family - all convictions which can make life somewhat difficult in the real world!

There was a Kindergarten near our house called 'Poltimore' and my mother took me there to enrol. I was not too co-operative. The headmistress was a Miss Monkton, an old lady with pince-nez glasses. She took them off and handed them to me.

'Take these glasses to that lady over there'

'I won't'

'We know what to do with little boys like that!'

A man came with a puppet theatre and performed 'Jack and the Beanstalk'. The clouds rolled down and Jack appeared to climb up into the sky. I was entranced by the magic of theatre and would remain so.

Move to Brighton (1944)

Downs County Primary School

Although my father had moved away from the Brethren, perhaps he felt he had not moved far enough. As the war neared its end he decided we should move to Brighton, where he had no friends or contacts whatever. We would live 'twixt sea and downs' and he would commute every day on the excellent train service to Victoria. Prices were at rock-bottom and he purchased a run-down terraced house with some bomb damage at 113 Preston Road, of which we would occupy the top two floors. We did not at first have access to the tiny walled backyard but across the road was the beautiful Preston Park which he said would 'make up for it'. There was a somewhat dangerous flat roof with a delapidated railing, opening from the stairs on the third floor, where one could hang out washing. The house was very noisy, being on the main road to London, backing on to a furniture depository with six lorries and beyond them the railway shunting yards, but as he explained, 'very convenient', since he could walk to the station. My brother and I were enrolled in Ditchling Road Primary School at the top of Stanford Avenue (which later changed its name to The Downs Primary School) and the choir at Saint Augustine's Church a short way up.

At Primary School we were taught folk songs. My girl-friend was Susan Sheen. We would stand up in front of the class and she would sing:

'Oh soldier, soldier, won't you marry me, with your musket, fife and drum'

and I would sing the bitter ending

'Oh no sweet maid I cannot marry thee for I have a wife of my own'.

A song about deception, betrayal and bigamy if one comes to think about it, yet teaching us something about life in such a quiet, gentle and humourous way that it stays in the recesses of the mind. In the sixties such folk songs became a no-go area and much wisdom lost in the process. English folk songs were often 'modal', in the minor with flattened sevenths and major sixths, whereas the scales taught at The Preston School of Music, to which I was soon to go, insisted on flattened sixths and sharpened sevenths, the European system. The English music of the first half of the Twentieth Century cultivated and revelled in this modalism, which permeates the music of Vaughan Williams, Warlock, Finzi, Holst, Delius, Ireland, Moeran and many others. I have never forgotten this and am still an unreformed modal person, not always noticeably, but very strongly if asked to indulge - for instance the film score for 'A Month in the Country'where the period setting of the early twenties and a country church made it irresistible!

Choirboy (1945)

St.Augustine's Church, Brighton

Bartholomew Hales ARCO had just taken on the post of organist and choirmaster at Saint Augustine's Church. He was only about five-feet tall but dignified, brusque and serious. Choirboys practised on Wednesday evenings from 6 to 7, and again on Fridays from 7.15 with contraltos, joined at 8.00 by tenors and basses. My father joined it as a tenor and my brother and I joined it as trebles. We sang everything: Victorian anthems, Elizabethan motets, Purcell, Wesley, Noble in B minor, Stanford in C, Bach, Mendelssohn duets, Bach chorales, Haydn, Morley, Gibbons, Tallis, Stainer, J.B.Dykes (slightly frowned upon), MacPherson, Parry - Mr. Hales introduced us to the whole range of Anglican music just as if we were singing in one of the great English cathedrals. He had retired from 'the City' we were told, had been an assistant organist to the prestigious George Thalben-Ball at the Temple Church and had even on occasion conducted some light opera at the Scala Theatre. He would never have told us this himself. He gave no encouragement, no praise, nor indeed censure beyond the occasional mild correction. He instructed and rehearsed the choir as necessary, chose the music, played the organ with minimum ostentation, and was in every way reliable, correct and utterly impenetrable.

One day he told my brother and I that we were to come to his home on Monday evenings at 7 o'clock for singing lessons. No money was involved. We arrived at his large detached house in leafy Surrenden Avenue, were ushered into the music room by his young wife Kathy and there put through a great variety of vocal exercises and gymnastics: 'Come let us see the sun rise up' (on a rising scale) and 'Now let us see the moon go down' (on a falling scale). We sang scales to 'Naw,naw' and 'Nah, nah' and 'Nee,nee'. We were taught breath control by taking in a huge breath and attempting to sing a whole verse of 'Crimond' (the 23rd psalm) in one breath. I became so expert at this that later I could sing two whole verses in one breath and when at 14 I was entered for the long plunge event at the Grammar School swimming gala, I floated miraculously for 3 minutes under water hitting the other end of the pool and becoming the all-time winner of the event- the only notable sporting achievement of my life! After the exercises we were taught arias such as Handel's 'Art thou troubled', Bach's 'Let the bright seraphim' and Mendelssohn's exquisite duet 'I waited for the Lord', which I adored. We became the leaders of the choir (Cantoris and Decani) often performing at weddings on Saturdays for a shilling, or two and sixpence if we sang a solo. My favourite solo was 'Love one another with a pure heart fervently' by Samuel Wesley.

The organ at St Augustine's was unusually fine. It had only just been built and installed at a cost of £32,000 - a 3-manual Morgan and Smith with 60 speaking stops, a simulated 32' pedal stop which made us shake in our shoes, tab stops, manual and pedal pistons with couplers, a solo tromba of resplendent power, and a Choir Organ 'Salicional' of exquisite delicacy. I was in awe of this great machine operated with such deadpan disinterest by the diminutive maestro. At the age of about 12 I summoned up courage to ask if I could try to play it:

'After choir practise on Friday'.

No surprise, no reaction, no expression.

He taught me the organ. Again no money was involved. Left hand with right hand together; left hand and right foot together; right hand, right and left foot together; all together. We set about the works of J.S. Bach, the organ sonatas of Mendelssohn, and the chorales of Cesar Franck. I worked and worked at his magnificent 'Chorale in A minor' in the hope of causing a reaction. I was amazed at my own temerity for daring to take on such a bravura work and thought at the least I would be reprimanded for overstepping my years. We got to the mighty ending with the pedals in octaves and full organ lifting the roof off, leaving the extreme silence one experience after extreme loudness. A slightly longer pause than usual.

'What else have you been working at?'

I never knew if he thought I was any good or not, but I became his assistant and was allowed to play first of all for funerals, then weddings, then communion services and finally for all the services when he was on holiday. He died at the age of ninety-six, nearly thirty years later, still playing the organ, but now at St John's Church in Knoyle Road. His wife phoned me to ask if I would make the funeral oration which he had requested.

'He thought the world of you, you know'.

I felt bewildered and ashamed, for I had hardly ever seen or spoken to him in all those years; just sometimes we would have a few words when he passed my parents' house, and one day he'd given me his own ancient,treasured copy of Stainer and Barrett's 'Dictionary of Musical Terms'. I prepared my oration for the funeral and arrived to find the big church full to overflowing with dark-suited, impressive-looking business men, none of whom I knew. Where had they all come from for a retired man of ninety-six? I mounted the pulpit, stared at the sea of faces and told them that Mr.Hales had taught me everything about singing and everything about organ-playing and sacred music. He had never requested or taken payment or thanks. I was deeply indebted to him and yet I regretted to say that I had never had the remotest idea what he thought or felt about anything. I recalled the most profound tragedy that he had suffered, when his twelve-year old daughter, Daphne, so delicate and pretty, was taken ill and died suddenly. I'd tried to find a moment to express my grief - yet I could not find a way of doing it. As everything else, he brushed it aside. Choir practises continued as normal, anthems announced, hymns listed. The little man remained dignified and impassive. As I left the church one of the tall, dark-suited ones addressed me.

'We are very grateful to you for your address- you gave a perfect description of a mason of the highest degree.' For so he was.

In 2006, a school-friend wrote: 'Brightonians may not realise that there is a Brighton link whenever they hear 'Walking in the Air', the much-loved song from the animated film, 'The Snowman' which is so often screened at Christmas. Howard Blake, the composer, attended Brighton, Hove & Sussex Grammar School in the 1950s, as I did myself, and I was fortunate enough to hear his already accomplished piano-playing whenever I visited his house or his organ-playing when I visited the nearby St Augustine's Church. Accordingly his music invariably brings a host of additional memories, even though the piece was written many years later.' [Brian Dungate]

Preston School of Music and my first music certificate (1946)

113 Preston Road, Brighton

My bedroom in 113 Preston Road was about 3ft.6ins. wide and should have been the kitchen. It was separated from the living room by an asbestos partition-wall on the other side of which was our upright piano. After I had gone to bed, my mother, with an enthusiasm enhanced by her twenty years of denial, would delve into her repertoire of piano music learnt in the early years of the century. My ear was next to the sound board and the volume was non-adjustable and loud. It was 1945 and I was 7 years old. I listened to Beethoven's first Sonata in F minor, to 'The Moonlight' in C-sharp minor and the 'Appassionata' in F minor; to Rachmaninov's C sharp minor Prelude, Tchaikovsky's 'Chants sans paroles', Rubinstein's 'Melody in F', Cecile Chaminade's 'Automne', Christian Sinding's 'The Rustle of Spring' and many of the Chopin Waltzes. The one I loved most was the A minor with the tune in the left hand. I was six and I wanted to play it more than anything in the world. Amongst ageing volumes of sheet music in the piano stool I found 'Ezra Read's Piano Tutor' with a diagram of a keyboard and all the notes labelled. I tried at first to play it by ear but couldn't find the right pitch. It struck me that if I could write the note names onto the piano with indelible pencil and then write them into the Chopin waltz, it ought to enable me to play it. It did, although the indelible pencil markings on the piano keys were not exactly welcomed by my parents! However, from the beginning I began to play music both by ear and by sight-reading and from the beginning I realised that it was possible to write down notes that turned into music.

I asked if I could have lessons, but my father initially resisted, so I was essentially self-taught - however a year later my mother took me four doors along the road to a house with an enormous ancient sign spelling out 'Preston School of Music' in faded gilt lettering where I met a Mr.Bonney Churcher in wing-collar, cravat with gold pin and waistcoat with watch and chain, a character straight out of Dickens. I was one of a stream of children and young adults exhorted to play scales with the correct fingering, to keep strict time and to work as hard as possible for the next exam. Lessons were 1s 3d for half an hour or 2s 6d for an hour and although I enjoyed them I never got to like the scales. In fact neither of us seemed to enjoy the piano practise side of things very much and I later realised that Mr.Bonney Churcher was more an organist than a pianist. Perhaps because of this my piano playing got off to a fairly slow start from a technical point of view.

'If only you would practise, you could end up playing the organ in Saint Paul's Cathedral' he would say to me, this being the highest form of musical attainment he could think of. He was wonderfully cheery and kind-hearted and really meant this, but I exasperated him terribly because from the beginning he would put a new piece in front of me and I would tend to read it straight away, so that when I came for the next lesson he couldn't tell whether I had practised it or not!

I loved to sight-read music and I loved to improvise, mostly in the key of D major or minor and I started to write down short songs and piano pieces, first on birthday or Christmas cards for the family and then for myself to play.

MARCH IN D (1949)

Scholarship to Brighton Grammar School.

The teacher in my fourth year at Downs junior school was the stunningly charismatic figure of Richard D. Webb ('Dickie' Webb) - pedagogue extraordinary, sometime playwright, Shakespearian actor, RAF hero, centre-forward for Southampton, poet, raconteur and form-teacher. In a grey and depressed post-war Britain of rationing, pre-fabs and dowdy clothes he would appear in brilliant Fairisle sweaters, loud check suits, yellow waistcoats and deafeningly-loud ties. He wrote us a play in Iambic pentameters, explaining blank verse and why the Bard had used it. The play was about The Globe Theatre. My life-long friend Christopher Geer was playwright William Shakespeare and I was principal actor Richard Burbage, singing a version of 'Greensleeves' to lyrics of Mr. Webb's own making:

'The masque is o'er, the play is done...'

All had parts suiting their own characters and this little production caused some attention, gaining a Sussex youth-theatre award. Dickie Webb gave us football trials and coached us as if professional, winning us the trophy for Best Brighton Junior School Team (in which I always played Inside Right); he divided us into groups and we built puppet theatres, writing our own plays for them; he divided us into further groups and we created newspapers; we were asked to invent languages and invent new vocabulary; we were encouraged to speak up for ourselves; to sign our names with a flourish; to write elegant letters; develop good manners; to reach out in every way. Dickie Webb believed in self-expression, creativity and freedom. My mother asked him if I was doing all right and he said:'The sky's the limit!' in a voice that would have kept Sir Donald Wolfit in obscurity. There was not one of us who would not have laid down his or her life for him had he but twitched one well-manicured finger.

One hour every week we sat in a radio room and listened to 'Adventures in Music' from the BBC, presented with the sound of a symphony orchestra, listened to attentively, perhaps for the first time? We were given glossy booklets with pictures of living composers: Richard Strauss who'd composed 'Till Eulenspiegel and his merry pranks' and was shortly coming to London to conduct it; Sibelius who lived in isolation in the forests of Finland and had written seven great symphonies; and Benjamin Britten who had just written an opera called 'The Little Sweep' which Norman del Mar was coming to Brighton's Theatre Royal to conduct and we were to be taken to see - for nothing! 'By courtesy of the Welfare State'. Dickie Webb arrived one morning laden with government-supplied music scores and taught us the songs so that we could join in and be part of it. It was something new and quirky with funny crushed notes and extra beats. We were living in a wonderful welfare-state of Free Song and Dance, Imagination and Inspiration - a great year to be alive, and a great country to be alive in!!

FIRST COMPOSITION

Since we were being asked to invent our own languages, to create newspapapers, to build theatres and in every way try to be creative, it is perhaps not surprising that I wrote my first complete composition around this time. I was aged about ten and for no reason that I remember wrote 'March in D Major', on manuscript music paper, and in ink. It had a minor secondary subject, an elaborate recapitulation and a triumphant finale with a running bass line in octaves. I cautiously took the manuscript along to a piano lesson to show and play to Mr. Bonney Churcher and he got very red in the face and puffed a lot and asked me if I had really written it:

'You mustn't lie to me sonny. It's very wrong to lie!'

At this moment an adult lady pupil arrived, whereupon he took the manuscript away from me and demanded that I play the march again to both of them from memory.

Which I did! And he was most surprised!

'Well, well sonny! You obviously did write it! Well, we're going to have to teach you harmony and correct progressions of the parts, and counterpoint and then perhaps even fugue! It's most unusual! I don't usually start to teach music theory to my pupils until they are at least 15 or so!'

Suddenly he was excited about teaching me and I was thrilled at the thought of learning. He ordered a textbook, Percy Buck's 'Practical Harmony', and my mother somehow managed to persuade my father to send off for it. Bonney was as good as his word. We worked through 6/4 chords, suspensions, plagal and interrupted cadences, the Neapolitan sixth, the diminished seventh, the grammar of classical music. Later he produced his own morocco-bound counterpoint textbook which he'd used as a student, probably as far back as the 1890s, and we worked through that as well- 1st species, 2nd species, 3rd, 4th and 5th, then canon and free, three-part counterpoint, moving finally to fugue and its complexities of subject and countersubject, augmentation and diminution, pedal and stretto. It is to Bonney Churcher that I owe my knowledge of harmony and counterpoint, instilled somewhere between the age of 10 and the age of 15.

I was 15 in 1953 when one day he asked me to visit. He had something to give to me. I arrived to find he was suddenly thin and pale and very grey. He presented me with his much-cherished album of Bach's 48 Preludes and Fugues - his most prize possession.

'Please, please work at it sonny and you'll end up playing at St. Paul's.'

But in mid-sentence he was seized by some appalling inner pain and couldn't continue. I left clutching the big book, which I still keep beside my piano - not realising that I would never see him again.

The bronchial pneumonia I'd sufferred since my ducking at the age of four still caused me trouble and I was often ill and confined to bed, sometimes missing important steps in my education. At home I would make imaginary towns amongst the bed-clothes, model plasticine and draw and paint. Fifty years later memories of this jogged back into mind when I read Robert Louis Stevenson's 'A Child's Garden of Verses', the result being both a song-cycle and an animated film.'The Land of Counterpane'.

The school had a visit one day from a talent-spotter from Brighton Art College and I was picked out for a scholarship - surprisingly not for acting or music but for painting. I went once on a Saturday morning and made an oil painting of whales and whalers but was suddenly taken ill and it was decided by my parents that I was doing too much and shouldn't return. Perhaps if I had I would have become an artist rather than a musician!

Many years later,in 2002, I applied for membership of The Chelsea Arts Club citing as qualifications my OBE for services to music, 600 musical works and Groves Dictionary's remark that I had succeeded as composer, conductor and pianist.

'But you are not an artist.'

'Isn't a musician an artist?'

'No, you have to prove that you can draw.'

I took along a pencil drawing I had made of my girl-friend Diahann Joseph and membership was instantly granted!

Solo soprano in Gilbert and Sullivan's 'Ruddigore' - as ROSE MAYBUD (1950)

The idyllic year of 1949 came to an end with the 11-plus scholarship exam. Many of our A-stream passed it, as I did, but because our house was on the west side of the London Road, I was sent to Brighton Hove and Sussex Grammar School for boys, up the hill on the Dyke Road, whilst most of my friends, including Chris Geer, went to Varndean, up the hill on the other side. My brother Philip had already attended the Grammar School for 3 years and was outstandingly succesful academically, coming top of the A-stream in all academic subjects and having to suffer shouts of 'swot' every morning. (It was even rumoured that he did not make a single mistake in Latin for four years!) BGS was considered to be a very good school, having only recently stopped being a private-school when Attlee's socialist government had nationalised it.

The somewhat forbidding-looking black-gowned masters of BGS knew nothing of glorious Dickie Webb and his boundless enthusiasm for the individual soul. They believed more in tradition, discipline, law and order, the armed services and above all in games of the team variety. The much-admired motto of the school was: 'Absque labore nihil' (Without work nothing). They had no school orchestra and a single, not terribly inspiring music master, Albert Chapman. He did however present a twenty-minute gramaphone recital of popular classics every Monday morning after prayers, an annual inter-house music competition and once a visit by professional musicians - The McNaghten String Quartet playing Debussy and Kodaly - a luscious introduction to the string quartet that instantly hooked me for life.

However, on my first Wednesday at BGS Albert Chapman took us for class music and asked if any of us sang in a choir. He explained that there was a well-established tradition of a yearly performance of a Gilbert and Sullivan opera, this year's being 'Ruddigore', for which we were to audition.

(The Misses Guille, two ladies from Guernsey who had occupied the ground floor of our house in Preston Road for the duration of the war had now finally returned home and this had meant that I had been moved to a big attic room of my own. Taking advantage of the fact that no one could hear me up there, I had started to sing scales just for fun, trying to go higher and higher every night. It amused me to see just how high I could go.)

So when my turn came to sing a scale for the opera audition I first sang a scale from middle C, then D, then E, F, G.

'Can you go higher?'

'Yes'.

A flat, A natural, B flat and finally a scale up to the top C, as in the famous 'Allegri Miserere'.

'Have you had singing lessons?'

'Yes'.

'Have you done any acting?'

'Yes'

'Would you like to audition for the lead role in the opera this term?'

'Yes'.

THE DIVA

The opera was 'Ruddigore', and the following evening I attended the first opera rehearsal amongst boys who seemed to be twice as big as me. I was 4 feet 9 inches tall. I sight-read the songs and got the part. Never, in all the musical achievements of my life, have I been so elated as that evening of my first week in senior school. For seven years I was to walk to school up and down Dyke Road Drive - a dark, steep hill alone alongside the railway, with small terraced houses on one side and a massive forbidding concrete wall on the other. It was extremely ugly, but, on the night I became an operatic soprano, Dyke Road Drive Brighton was a place of wonder and delight as I sang and ran my way home.

I had no idea that I was replacing anyone else - no idea that an older boy was mortified and immediately moved away to a private school by furious parents. I had no inkling at all of how much being talented can hurt people. I played the part of Rose Maybud whilst Robin Oakapple was played by Johnnie Lee, rumoured to be the son of the famous entertainer Vernon Lee, whose picture hung in the National Portrait Gallery. The show attracted the attention of the press:

'As Rose Maybud, 11-year old H.D.Blake gave a remarkable performance for a boy of his age. He started with the natural advantage of a sweet soprano voice, but the fun he extracted from the maiden's etiquette book was delightful. The droll effect of the duets between Robin Oakapple and May Rosebud were heightened by a difference of more than a head and shoulders between them.'

AN INTRODUCTION TO CHAMBER MUSIC

Walking home after my operatic debut as the lead soprano in 'Ruddigore' aged 11 I was caught up by one of the orchestra, a violinist called Jack Millard, who happened to share some of the same walk home. When I told him that I played the piano and could sight-read he asked if I'd like to play trios one day - his friend John was lead-cellist in the Sadler's Wells Opera Orchestra, he said. I was most impressed by this and couldn't wait to try it. My mother agreed to my going over and I arrived at his parents' big old house in Clermont Road. We embarked on some Hummel trios and the sound of violin, cello and piano was just marvellous to me. It was my first experience of chamber music and I found that I could hold my own with two grown-up professionals, which to me was quite revelatory.

Suddenly into the room swept an imposing middle-aged lady dressed all in black who stopped us in our tracks:

'What on earth are you doing playing MY trios with a small boy?!'

'He plays very well Mother, just listen.'

'I have no intention of listening to a small boy usurping MY position in The Millard Piano Trio!'

My discovery of the joy of chamber music had thus been very short-lived since I was not permitted to play with them again. Yet the sound of it had entered my soul for ever. I struggled to sketch out a piano trio of my own with a first movement (Allegro), a slow movement (Andante) and a scherzo (Presto). Some years later Philip Pfaff of Chappells published the first movement under the title Fantasy-allegro for piano trio at the same time publishing Burlesca for violin and piano which I had written to be played in the house music competition by a boy called Richard Annells, and 'Party Pieces' for piano, which I had composed as a birthday present for a girl-friend, variously called Doreen or Frances!

Philip Pfaff was in fact also interested in the slow movement but felt that it needed more work. He returned it to me with some written observations, along with the scherzo fragment. This turned out to be fortuitous because in 1964 Chappell's' Music of Bond Street burnt down and most of the manuscripts were lost. In 2014 I rather extraordinarily received an inquiry for the 'Fantasy-Allegro'. This caused me to dig out the ancient sketches and, after this immense gap of nearly 60 years I set about extending the first movement (Allegro), rewriting the second movement (Andante con moto) and reconstructing the third (Scherzando), giving the completed work the name Fantasy-Trio - Piano Trio number 1

DAVID SHAW

There had been a third contender for my role in 'Ruddigore':

'Shaw's Mad Margaret was another succesful example of casting. There was an Ophelia-like poignancy about the mad girl scenes followed by the extraordinary contrast of diverting comedy with Sir Despard Murgatroyd'

David Shaw was NOT removed from the school by his family for failing to gain the lead part, but on the contrary became a friend and a great musical influence on me. He was a year older and very tall and thin. 'How long is Shaw?' boys would quip. Shaw could play the organ really well and improvise fluently on the piano. He had been brought up with the idea of theatre and opera, his father being a passionate performer of Gilbert and Sullivan and president of the Brighton and Hove Gilbert and Sullivan Society devoted to it. The family owned 'Shaw's Stores' a large department store in Hove and they lived in a fine detached house off the Dyke Road with a TV, radiogram and grand piano. Shaw was 'musical' and was 'going to be a musician'.

I was in awe at the enormity of such an ambition having recently seen the film 'Prelude to Fame' with Jeremy Spencer, about an uneducated 9-year old Italian peasant boy destined to be a great conductor - one day he somehow wanders from the farmyard into the garden of a palatial house and hears orchestral music for the first time, the first movement of Beethoven's 5th that is playing on a gramaphone. In a trance he walks up to the glistening Steinway, sits down and with just the hint of a frown reaches out instinctively and plays the whole thing back by ear.I left the cinema realising that however much I might like music I'd never be THAT good and when eventually I became a professional musician it was to my own considerable surprise. 'The camera never lies' they used to say in those innocent days.

Music was just my hobby, but I started spending a lot of my free time on it, playing piano duets with Shaw every Saturday. First, things like Arthur Benjamin's 'Jamaican Rhumba' or Walton's 'Popular Song' from 'Facade'; then arrangements of orchestral works like Elgar's 'Enigma Variations' and overtures and symphonies by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. A year or two later Shaw's grandmother died, bequeathing a larger house and another piano, which opened up further possibilities. Shaw acquired a two-piano version of Brahms' 2nd Symphony, Rachmaninov's gorgeous Suite opus 17, works by Ravel and Faure, Mahler and Stravinsky. He also bought records and played them to me to guess the composer. I was quite good at this because I listened endlessly to BBC radio, but I remember that it was he that introduced me to Delius's 'On hearing the first cuckoo in Spring', a music of the sort of Englishness that gives one an eternal yearning for trees and water and the countryside. Bartholomew Hales took me to hear none other than Sir Thomas Beecham in the Dome, sitting down to conduct it and audibly swearing at the orchestra, who seemed to love it - and him. I was so smitten with the piece that I transcribed the score for piano and some twenty years later it would influence me to buy a fabulously picturesque water mill, where I would constantly suffer from colds and bronchitis, a problem that would never occur to one when listening to such ineffable music.

We were spoilt by the quality of artists visiting our town. Shaw's father was also a member of the Brighton Philharmonic Society and his card permitted us to creep into Herbert Menges' Sunday morning rehearsals in the Dome to see soloists like Solomon, Shura Cherkassky, Myra Hess or Clifford Curzon, singers like Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, or cellists like Paul Tortelier, whilst the marvellously-informed Shaw would keep up a running commentary with endless ironic asides that would keep me spellbound by their effrontery. Once, via the school, we were allowed into a rehearsal of 'The Marriage of Figaro' at Glyndebourne which was to hook Shaw on serious opera for life. After Oxford he was taken on by Covent Garden Opera and groomed as repetiteur and assistant conductor, once directing a performance of 'Clemenza di Tito' there before leaving to live in Germany and work in Ulm and Bayreuth. I was never attracted to opera in the way he was, and gradually our tastes and opinions on music diverged. To me the most profound music of the great composers is found in their string quartets and chamber and instrumental music, in their symphonies and choral-orchestral works. When one writes for theatre, the music serves a different master, getting characters on and off the stage, whipping up the excitements of marriage and betrothal, victory and war, betrayal and violence, politics and death - nearer the extrovert world of Hollywood and glamour than the inner world of the spirit.

Solo soprano in Edward German's 'Merrie England' - as BESSIE THROCKMORTON (1951)

1951 was the year of The Festival of Britain and to celebrate this the school put on Edward German's mock-Tudor operetta 'Merrie England', which contains a showy coloratura part for soprano - Bessie Throckmorton. Apart from several top B flats it contains a cadenza covering a range from G below middle C to high F in alt, two octaves and a minor seventh higher. On auditioning for the part, and probably due to my endless high-note practising in the attic, I found I could do this cadenza. At the first performance the somewhat conservative Head of Junior School, Milton, asked what note I was singing and when I told him declared it 'unnatural' and got quite upset:

'Boys do not sing up to that pitch. It's unheard of!'

But there it was, and at a time when a singer called Amy Camus called herself Yma Sumac and had a popular success with 'Hymn to the Sun God' which extended over four octaves, I was unabashed. Perhaps Mr. Milton did have a point because on the third night performance the top E flat for some reason didn't sound and I was left alone at centre stage in total silence wondering what I should do. Had my voice suddenly broken because of strain? The conductor, Albert Chapman thought not and started the orchestra off again from the top. This time all the notes came out - to rapturous applause!

Synchronicity is Jung's word for the occasion of coincidence where the chance of that coincidence occurring is higher than the reasonable odds. A lady named Violet Whitley, well-bred but of what used to be called 'reduced circumstances', had rented our basement flat and had realised that I had an insatiable thirst for music (it would have been difficult not to since the piano now stood directly over her head!) One day she called me down to the basement.

'I have some old books you might like'.

A large pile of heavy but beautifully-bound volumes were stacked just inside the door. The first one contained the complete works of Chopin in different editions, bound together. The next contained a Leipzig edition of all the Beethoven sonatas, the third Greig and Debussy, the fourth Bach - and so on. My mother and I speculated that she might have studied piano in Germany some time before the war. The books appeared to have come from Leipzig and were signed by a Violet Beaumont, which we felt must have been her maiden name, but she was unforthcoming about her history. A chance remark about Clement Attlee intensified the mystery.

'He went to Harrow. He's my cousin'.

What was a person with such elevated connections doing in our basement?

I welcomed these books with open arms and began to consume them from cover to cover. For me it was a miraculous gift, a treasure trove, since there would have been no way that I could have afforded such a marvellous library, or have even persuaded anybody for my need to have one.

The town of Brighton was bursting with music for all to hear. Military bands played at the band-stands on the promenade; trios of violin, cello and piano played in palm-court lounges and pier tearooms - 'Chanson de Matin' and 'Salut d'Amour' of Elgar, 'The Wedding of the Painted Doll', 'Valse Triste' by Sibelius, 'In the Shadows' by Herrmann Finck - the standard repertoire of light music, often written by the greatest of composers; a wonderful ancient harp and violin duo echoed through The Lanes; in cinemas there were Wurlitzer organs that came up on lifts between feature films played by men in pink dinner jackets; at the Regent Dance-Hall was Syd Dean's All-Star Dance Band; Sadler's Wells Royal Ballet would come to the Hippodrome every year and the Carl Rosa Opera would come to the Essoldo.

Some evenings my mother played second violin in the scratch Kingscliffe Light Orchestra, which David Shaw and I sometimes attended and found hilarious. Mr Whitcombe, the ageing conductor, would lose concentration at times and lose his place, whereupon the leader, Madame Pordes, would become furious and stamp her foot. Clem Rosling, the clowning percussionist, would add unwanted motor horn 'parps' to wake him up and in difficult string passages the volume of sound would curiously diminish as the less confident players made sure their bows didn't touch the strings. George Moore would play the Trumpet Voluntary and go a brilliant shade of scarlet and Major Keen would triumph over his huge handlebar moustache and play an oboe solo. Sometimes I had to control my merriment on being asked to sing a solo: Handel's 'Art thou troubled?' or Bach's 'Let the bright seraphim' or perhaps something lighter like Johnson Oatman's 'Count your blessings one by one.'

Solo soprano in G&S's HMS Pinafore as JOSEPHINE THE CAPTAIN'S DAUGHTER (1952)

The third soprano role of my short singing career was also the most fun - Josephine the captain's daughter in 'HMS Pinafore'- with David Shaw as Buttercup and a marvellous singing discovery for Ralph Rackstraw in the person of John Mason, later changing his name to Ralph Mason and becoming principal tenor of the D'Oyly Carte Opera, Freddie in 'My Fair Lady' at Drury Lane and a star of The Welsh National Opera. Although we were the same age in 1952, his voice had broken and mine hadn't.

INVESTIGATING LITERATURE

'Jolly' Jack Smithies was our third-year form master and English teacher. He was strongly dismissive of Gilbert and Sullivan and attempted to move us sharply forwards, extolling the excellence and originality of T.S.Eliot and Alfred J.Prufrock:

'Let us go then you and I When the evening is spread out against the sky Like a patient aetherized upon a table'

But I found this funny and somehow shocking, not reverent enough, as Robert Graves warns in 'The White Goddess':

'Skilful parody of a poem upsets its dignity,sometimes permanently as in the case of the school-anthology poems parodied by Lewis Carroll in Alice in Wonderland.'

I was prepared to believe Eliot to be a great poet on one line of surpassing beauty:

'Sweet Thames run softly till I end my song.'

But then I found this to have been by Spenser and thought it to be an outrageous plagiarism on Eliot's part. All his poetry pokes fun at other poets, rather as jazz musicians quote and trivialise snippets of the classics - out of something between admiration and envy.

In music I felt rather the same about Britten, that he satirised the melodies of others rather than achieve his own. Even at that age I believed that the defining merit of a composer lay in his ability to compose great melodies. Jack Smithies was smitten by Britten and once invited me to accompany him to the first London performance of 'Noye's Fludde' in Southwark Cathedral, conducted by the composer. I was thrilled by the arrangement of the Victorian hymn-tune 'Eternal Father strong to save' but the rest left little impression on me.

Jack Smithies also introduced me to Proust in English translation which I thought quite wonderful and I attempted an essay in the same style. The wonderful BBC Third Programme at that time broadcast the whole of 'A la recherche du temps perdu', dramatised with the greatest living actors and this made a huge impression on me. I toyed with the idea of becoming a writer and rather ambitiously attempted a short story in the Proustian style. Mr. Pascoe, my English teacher at that time commented: 'somewhat recondite!'

Solo contralto in G&S's 'Yeomen of the Guard' - as DAME CARRUTHERS (1953)

..and a family disaster

My dear brother Philip was three years older than me and brilliant in many ways. He mastered the skills of Meccano and somehow acquired an enormous second-hand assembly of every existing manufactured Meccano item. When shown a Bren gun in the school cadet force he came home and created a prototype that he claimed could fire more bullets per minute than the real thing! When we played Monopoly he created his own game called 'Managing Director' with dice, instructions, stocks and shares and boards, in all innocence sending it off to a leading games manufacturer who later were to manufacture it as their own invention. When introduced to model-making he created an extraordinary 'Flying Wing' which we watched him fly in the park. When I had an interest in puppet theatres he made one out of Meccano, writing a perfectly-construed verse play about National Savings Certificates for us to perform. When we visited London he decided that the traffic was badly-organised and drew up a comprehensive road reconstruction plan. He had a tremendous gift for languages, the Latin master making the astonishing claim that he had not made a single error until the 4th year. He naturally gained a first class A-level in it as well as in French and German, later adding Italian, Spanish and other languages including Arabic and Hebrew which he read at Oxford. He enjoyed scouting and cadets, was a good runner, a good swimmer, and an excellent fast bowler though never being asked to join a team. For some reason he was always alone and I don't remember friends coming to the house to play with him. Something was wrong. His relationship with our father deteriorated and at sixteen there were frequent word-fights at Sunday lunch-time ending in screams, tears and locked doors.

His problems were about belief. He believed in Christianity, as he had been instructed, and he believed that he should 'honour his father' - but unfortunately found that he didn't agree with him. If anything he believed in what his father had believed when he was born - the tenets of the Plymouth Brethren, which belief system was still pretty well in operation in the person of our mother. Honouring her husband she had accepted his professed new Church of England outlooks but without believing in them. She attended Saint Augustine's as we all did, but, as she told me years later, there were many ideas she found hard to accept, going to war certainly being one of them, and this conflict of belief in his mother and father had started to affect their elder son.

He was about to start his last year at school when he announced to our father that he was a conscientious objector. Three days later he imparted this information to our BGS headmaster, Harry Brogden, as well. It would mean that he would cease to belong to the Combined Cadet Force in which he had been made a sergeant, and that he would oppose doing National Service, which was still in operation. Harry Brogden saw this as a black mark for the school and himself - letting the side down.

So my father and his eldest son argued, the headmaster argued and pressure was put on Philip from all sides.

The worst happened and he collapsed into a nervous breakdown, falling into a state of catyleptic trance for three days. His eyes were open but he did not speak or move, although I learnt later that he could hear everything we said. Our doctor came to look at him, then a psychiatrist or two, then a Mr.Combridge who ran The Crusaders, then the vicar and a curate and two school-teachers. It was decided that he must be moved to a psychiatric hospital for treatment and my father signed a form giving his permission. Mother and I did not agree. We said that his father had been bullying him for days on end and that he should just be left alone and would recover. But nobody listened or took any notice of us.

Philip was sent first to the general hospital in Brighton and then to Hurstwood Park, a specialised mental hospital out in the countryside. Once away from my father he recovered rapidly, but they wouldn't let him leave. On 5th October he decided he had had enough, discharged himself and headed up the road towards London, but he was picked up by police and taken back, and to make sure he didn't 'escape' again, locked in a cell. He was effectively 're-imprisoned'. It got worse. They decided to give him electric shock treatment. How could they know about Philip and his brilliant mind, or the lethal cocktail of charm and fanaticism that fuelled my father's brain? Nobody inquired. A year later the director of the hospital played chess with Philip. He told us that as far as he could see there was nothing at all the matter with him and remarked on his high level of intelligence.

'He shouldn't have come here at all' he said, but by then it was far too late. Everything changed. Not rapidly but bit by bit, like water dripping on stone. You don't notice you've changed but you have. Philip was never the same. He had always been a loner, but then a lot of this was because of being so clever, which cut him off from people or made them foolishly envy him. I determined not to be clever, or if I was, to conceal it. He never really came back home. The psychiatrists advised him not to. I lost my only brother and the house felt empty without him. He seemed to blame me to some extent for his collapse and this made me sadder than anything else, since I couldn't understand why he should think it. For a while he stayed with Dickie Webb and his wife who were very kind, but staggeringly was then called up for National Service. A year after the authorities had had him declared unstable they were putting him into uniform as an A1 specimen of young manhood. My confidence in these authorities dropped below zero. The effect on me was a total loss of belief in institutions: the church; doctors and hospitals; teachers, schools and universities; Freudian psychiatrists; families and relatives and so-called friends. I had seen them in action when there was a crisis and they had notably failed.

Mother was constantly visiting my brother in hospital and finding it difficult to look after Grandma as well. I sat with her quite a lot which I liked, but Horace had found an excuse for her to go and on 17th October he persuaded mother to put her into a nursing home. Sometimes she managed to visit us after that, but she died the following year. I wasn't invited to the funeral, because my father thought 'children shouldn't go to funerals'. I wish I had been there to pay my respects, I had been so fond of her. One effect of this was that somehow I no longer wanted to sing or play the organ, because I no longer wanted to go to church.

My brother was brilliant in many ways. He mastered the skills of Meccano and when shown a Bren gun in the school cadet force came home and created a prototype that he claimed could fire more bullets per minute. When we played Monopoly he created his own game called 'Managing Director' with dice, instructions, stocks and shares and boards, in all innocence sending it off to a leading games manufacturer who manufactured it as their own invention. When introduced to model-making he created an extraordinary 'Flying Wing' which we watched him fly in the park. When I had an interest in puppet theatres he made one out of Meccano, writing a perfectly-construed verse play about National Savings Certificates for us to perform. When we visited London he decided that the traffic was badly-organised and drew up a comprehensive road reconstruction plan. He had a tremendous gift for languages, the Latin master making the astonishing claim that he had not made a single error until the 4th year. He naturally gained a first class A-level in it as well as in French and German, later adding Italian, Spanish and other languages including Arabic and Hebrew which he read at Oxford. He enjoyed scouting and cadets, was a good runner, a good swimmer, and an excellent fast bowler though never being asked to join a team. For some reason he was always alone and I don't remember any friend ever coming to the house to play with him. I don't remember a girl friend of any sort either, although I know he would have liked one, at one point taking a course of dance classes at Arthur Murray's in the hope that this would improve his chances. On the day that I first set off for the Grammar School I asked if he would walk with me. I was really nervous about going there, but he refused, and for seven years I walked up and down the hill alone.

Something was wrong, either with him or with the school. Although for a while we sang together in the choir and he would sometimes help me with my homework, we never went on holiday together and rarely played together. The relationship with our father deteriorated and at 16 there was a regular fight-fixture every Sunday lunch-time ending in screams, tears and locked doors. He accused my father of betraying his beliefs and I suppose he was right. My father, though professing to be Church of England was still steeped in Brethren ideology. He hadn't counted on his children entering into the spirit of England to the extent of inventing machine guns and capitalist-inspired board-games. He didn't believe in any of that.

'So why do you pretend to be Church of England if you don't believe it?' my brother would ask him, and this would drive him to a fury. The answer really was that he now preferred normal life, loved singing anthems in the choir, loved painting and amateur dramatics and loved having joined the mass of society after 42 years of being thought odd.